A Roadmap for the Cross-Border Data Transfers Debate

Published: September 15th, 2017

Jon Doe commits a crime in country A. Digital evidence pertaining to the investigation of that crime is stored on the perpetrators electronic devices, which are located in Country B. Some additional evidence is stored in servers owned by an email service provider (ESP). While the ESP is registered in Country D, its servers are physically located in Country E. In the age of digital communications and cloud computing, law enforcement agencies are called to delicately maneuver this web of jurisdictions in order to obtain necessary evidence and run effective investigations.

The traditional approach has also been to rely on mutual legal assistance arrangements (MLAs) namely concluded through bilateral and multilateral treaties. These agreements lay the foundations for the gathering and exchanging of information in the enforcement of public or criminal laws. For example of a multilateral arrangement consider the 2003 Agreement on Mutual Legal Assistance between the European Union and the United States of America. For a bilateral example consider the Treaty between the Government of the Republic of India and the Government of Canada on Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters which was signed in 1994.

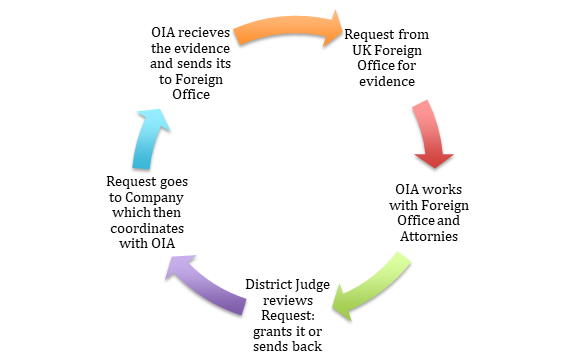

The 21st century’s move towards digital communications, online services, and cloud computing has complicated traditional legal cooperation in this space. The slow pace of the current MLA process for cross-border data requests has frustrated criminal investigators in many countries. Consider for example a typical process for legal assistance between the UK and the US as it currently stands. The UK Foreign Office sends a request for communications content data by a US company to the US Department of Justice Office of International Affairs (OIA). OIA works with the UK Foreign Office to ensure the request satisfies US legal standards and then works with a US Attorney to send the request to the District Court either in the D.C. area or in the jurisdiction where the evidence is held. The judge reviews the request and grants its, or sends it back to OIA for further iterations with the UK Foreign Office. If granted the request goes to the company, which sends a response to OIA, which checks the response and in turn sends the response to the UK (see graph A below).

The inability of companies to respond directly to the requesting country, even though the request has been judicially approved, significantly slows down the process. Moreover the need of the requesting Country to comply with the criminal standards in the requested State adds further frustration. As the European Commission noted in a recent “inception impact assessment” report on the issue:

“While a national request to service providers takes in general a few days at most, MLA requests to the U.S. as the main recipient take around 10 months on average and require significant resources. In such cases, the evidence transmitted is often outdated or comes too late... Through direct cooperation between authorities in EU Member States and service providers in the U.S., which is possible under U.S. law for non-content data, the latter receives more than 100,000 requests per year, compared to about 4,000 requests under the E.U.-U.S. MLA Convention”.

To this one needs to add the opacity that is the result of the storage practices of ESPs. The U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) of the U.S. Department of Commerce, identifies Cloud Computing as a “model for enabling ubiquitous, convenient, on-demand network access to a shared pool of configurable computing resources (e.g., networks, servers, storage, applications, and services) that can be rapidly provisioned and released with minimal management effort or service provider interaction”. At the heart of the model thus stands the idea that the physical storage of data may span multiple servers and thus multiple jurisdictions. The hosting company may not even be aware where a particular email is stored at a particular time. The (un)territoriality of data thus introduces a new challenge to traditional conceptualizations of jurisdiction. See in this regards the comments raised by the Group of Experts that drafted Tallinn Manual 2.0 (p.68):

“The experts noted that it sometimes may be impossible or difficult to reliably identify the State in which the digital evidence or other data subject to extraterritorial enforcement jurisdiction resides. They agreed that international law does not address this situation with clarity. Therefore no consensus could be achieved as to whether a state may exercise extraterritorial enforcement jurisdiction in such cases by taking law enforcement measures regarding that evidence or data.”[1]

In this short blog post I wish not to tackle this complex issue of jurisdiction. Instead I hope to map out recent developments in States’ practice to provide scholars entering the field with some broad background into the current state of affairs.

-

The United States:

- The Aftermath of the Microsoft Ireland Case- This past May the Senate Judiciary Committee ran a live-streamed hearing on Cross-Border Access to Data (good summaries of the debates are available here and here). The interest in running these hearings was sparked, in part, due to a unanimous decision from the Second Circuit’s in the Microsoft Ireland case (July 2016). The Second Circuit found that the US warrant authority pursuant to the Electronics Communications Privacy Act only extended to data that is physically located in the US. In that particular case the U.S. Government sought emails as part of a narcotics investigations from users whose accounts were located on Microsoft servers in Ireland. On 13 October 2016, the U.S. Government filed a petition for an en banc rehearing by the Second Circuit but it was denied on a 4-4 vote. On 23 June 2017, the U.S. Government filed a petition for a writ of certiorari with the Supreme Court. On 2 August 2017 the AGs of 33 States plus Puerto Rico filed a bipartisan amicus urging the Court to grant the cert. Since the Second Circuit decision, at least 10 different magistrate judges issued opinions rejecting the Second Circuit’s position. These include decisions from the Eastern District of Pennsylvania (February 2017), the Eastern District of Wisconsin (February 2017), and the Middle District of Florida (April 2017). More importantly is an August decision from the Northern District of California (NDCA) concerning a similar application from Google. This decision is noteworthy given the fact that most of the tech companies are located within the jurisdiction of NDCA. Senator Garssley (R, Iowa) of the Judiciary Committee has said that a legislative fix to the Microsoft Ireland case is coming up the pipeline, and will hopefully be put to a vote before the end of the year. In the meanwhile this split in court decisions is making it more likely that the Supreme Court will approve the writ and grant the cert.

- Rule 41 and Hacking as an Alternative to Cross Border Requests- Another development in the U.S. context concerns the Amendment to Rule 41 of the Rules of Criminal Procedure and Evidence, which authorizes a magistrate judge to issue warrants for remote searches (or the acking of devices) outside their district (all over the Country, and indeed the world) in cases where the media or information was concealed (i.e. in the context of user anonymizing technologies, such as ToR) (see more information here and here). This amendment follows a controversial hacking operation launched by the FBI in 2015 known as the “Playpen Investigation” and relates to a crackdown on consumers and producers of child pornography. The global investigation ended up hacking 8,700 computers in 120 countries, without the latter’s consent or knoweldge. There has been an academic skirmish on the Stanford Law Review, concerning hacking as an alternative to cross border data transfers - with Ahmed Ghappour writing “Searching Places Unknown: Law Enforcement Jurisdiction on the Dark Web” and Sean Murphy and Orin Kerr responding with “Government Hacking to Light the Dark Web: What Risks to International Relations and International Law”.

- The USA-UK Agreement- The US and the UK have been negotiating a bilateral agreement, the text of which has not been made public, that would allow the two governments to request for communications content data directly from the ESPs without having to go through State authorities or Courts. This is what some coin an “expedited MLA”. The Blogs Lawfare and Just Security have recently hosted a debate over the adequacy of the agreement and the extent to which it will protect the data privacy of the citizens of both countries (see here, here, and here).

-

The European Continent:

- Mutual Recognition: The European Investigation Order of 2014, which entered in force this past June, puts an emphasis on the principle of mutual recognition for judicial decisions when it comes to obtaining evidence for use in criminal proceedings. This directive applies to all EU countries except Denmark and Ireland, which are not taking part. The United Kingdom decided to participate in the proposed Directive. It replaces the Convention on Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters (MLAC), which was adopted as a European Council Act on 29 May 2000. As part of the move towards “mutual recognition” Commissioner Jourová announced her intention to put forward proposed legislative measures for adoption by the Commission in early 2018 which will ease the way by which European law enforcement authorities may directly request tech companies to provide them with electronic evidence. The Commission is considering one of three options: (1) the least intrusive option involves allowing law enforcement authorities in one member state to ask an IT provider in another member state to turn over electronic evidence, without having to ask that member state first. The decision to cooperate would be left to the companies’ discretion; (2) the second option would see the companies obliged to turn over data if requested by law enforcement authorities in other member countries; (3) the most intrusive option concerns situations where authorities do not know the location of the server hosting the data or there is a risk of the data being lost. In such scenarios the Commission is contemplating the power to compel companies to identify the relevant server and the owner of the data (including by breaking encryption, anonymization, and other privacy-enhancing tools).

- Additional Protocol to the Cybercrime Convention- the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime was the first treaty to address computer crimes by harmonizing national laws and increasing cooperation amongst nations. It was signed on 23 November 2001 and became effective on 1 July 2004. It was drawn up by the Council of Europe and as of today 55 countries have ratified it (with additional four signing but not ratifying). The Convention is open for accession by non Council members, though key countries such as India, Russia, and Brazil have refused to adopt it. In November 2016 in a meeting of the Cyber Crime Convection Committee a set of recommendations were adopted as part of discussions concerning effective responses to the challenge of “cloud computing”. One of the recommendations included the launching of negotiation for an additional protocol to the Budapest Convention to cover “solutions on criminal justice access to evidence stored on servers in the cloud and in foreign jurisdictions, including through mutual legal assistance”. The Cloud Evidence Group is now discussing the content of such a protocol and additional information is available here.

- THE CJEU NPR Decision: another alternative to the MLA problem has been the signing of particular subject matter agreements for the transfer of data and cooperation in particular areas. One such example is in the field of Passenger Name Record (PNR) data, which concerns data collected by air carriers through their automated reservation systems and departure control systems. In July the Grand Chamber Court of Justice of the European Union issued opinion 1/15 which concerned an agreement between Canada and the European Union on the transfer and processing of Passenger Name Record (PNR) data signed on 25 June 2014. The Court found the agreement incompatible with Articles 7 and 8 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms (concerning the rights of individuals for protection of their personal data). The judgment lays the foundations for any future automated sharing of such bulk datasets between individuals and agencies within the EU and the authorities of non-EU member States. For further reading see here.

- Non-Western Responses to the MLAT Problem: As we have witnessed, the western response to the MLAT problem has been to suggest reforms to the existing framework, such as “expedited MLA” and “mutual recognition” (for more proposals see e.g. here, here, here, and here) or extraterritorial enforcement (such as remote hacking and corporate backdoors). Outside of the Western hemisphere, however, the solution has been data localization. By compelling any company operating in your territory to also store data locally, the Country both increases its capacity to enforce its jurisdiction on the evidence those companies store, as well as protect its citizens from non-consensual transfer of their data. China adopted a new cybersecurity law, which included data localization measures, in April (more information is available here, here, and here). Indonesia, Russia, Brazil, India and Iran have all taken similar legislative measures (see this 2014 piece on the “Growth of Data Localization Post-Snowden”). Some even suggest that the EU General Data Protection Regulation is a “data localization” regulation in disguise. There has been significant criticism by lawyers, human rights advocates, and technologists on the impacts of data localization on the internet (see here, here, here, here, and here).

- The United Nations: The U.N. Security Council adopted Resolution 2322 on December 2016. The Resolution in operative clauses 3, 4 and 9 calls on all member States to cooperate in intelligence sharing and data transfers between law enforcement in the fight against terrorism, including through amendments to national legislation. Operative clause 13 is specifically devoted to the “review and update” of the MLA regime “in light of the substantial increase in the volume of requests for digital data” across borders. The UNSC subcommittee on counter terrorism (CTED) is in charge of submitting a report by the end of this year on the ways by which countries may implement this resolution. CTED has solicited information form Member States and civil society and in June held a two day technical consultation at the UN Headquarters on good practices for cross border data transfers.

For those interested in the topic Georgia Tech runs a “Cross Border Requests for Data” Project. In May the University ran four panels at an event titled “Surveillance, Privacy, and Data Across Borders: Trans-Atlantic Perspectives” (the panels were all live-streamed and the videos are available online). The topics discussed ranged from how to reform MLAs, the pending US-UK agreement, international law and cross border data requests and hacking operations. The May sessions were then turned into a symposium on the LAWFARE Blog, which is highly recommended. Earlier in January Georgia Tech ran a smaller event in Brussels, which was then used to launch a series of academic papers on cross-border access to user data.

[1] Note that the Tallinn Manual experts nonetheless go on to “adjudicate the territoriality and extraterritoriality of several situations where the data storage location is known”. For an analysis and criticism of the Tallinn Manual’s approach in this regard see the fascinating recent article by Kristen E. Eichensehr, Data Extraterritoriality, 95 Texas L. Rev. 145 (2017).